How to read chord symbols in 3 easy steps

What is a chord symbol?

A chord symbol is a shorthand way of describing the notes that make up a chord. Chord symbols are often used for notating the harmony of lead sheets or chord charts online. They are useful because you don’t have to write every single note of every chord on a stave using traditional musical notation. It’s up to the musician to interpret what the chord symbols mean and to play them appropriately on their instrument.

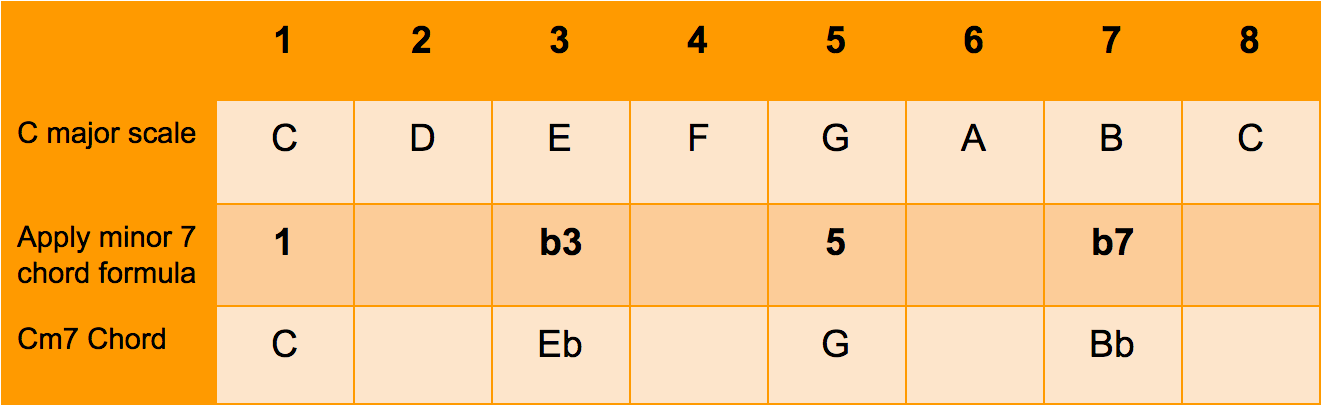

Chord symbols indicate chord formulas

A chord formula is a sequence of numbers that shows us which notes from the major scale have been used to make up the chord and how they have been altered. A Cm7 chord has the formula 1 b3 5 b7. This formula indicates how we have altered the notes from the C major scale to create a Cm7 chord.

Chord symbols can seem extremely confusing the first time you see them. They can be full of funny little symbols and numbers, but if you know how they work, they are easy to interpret. Here are three easy steps to get your head around reading chord symbols:

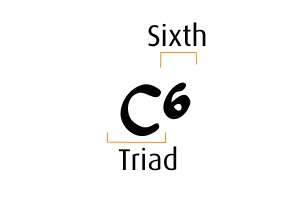

Step 1: Start with a triad

At the heart of most chords is some form of triad. This is a three note chord and is usually major or minor, although sometimes we come across diminished or augmented triads. A triad is formed by stacking two different third intervals on top of each other.

A diminished triad is where we take a minor triad and flatten the fifth by one semitone (we’re making the interval smaller by flattening it, so think ‘diminishing the size of the interval’). An augmented triad is where we take a major triad and sharpen the fifth by one semitone (we’re making the interval larger by sharpening it, so think ‘augmenting the size of the interval’).

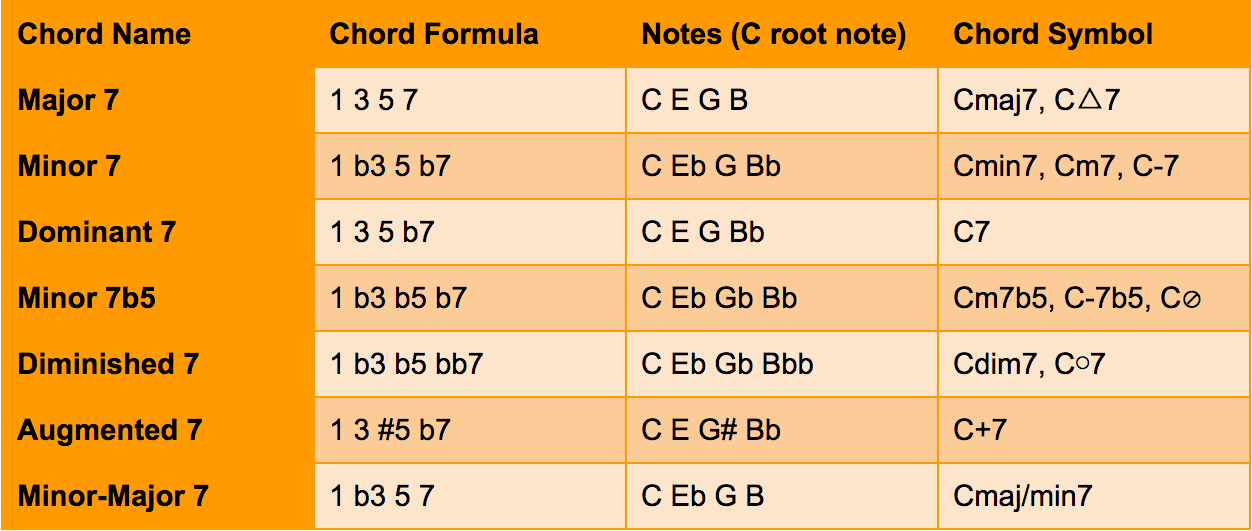

Step 2: Turn it into a seventh chord

If we take a triad and stack another third interval on top of it, we end up with a seventh chord. This is indicated in the chord symbol by adding a ‘7’ to the end of the letters that indicate the triad. Different seventh chords are formed by adding different qualities of the 7th scale degree to the major or minor triad (either the 7th, b7th, or bb7th scale degree). The three most common seventh chords you will come across will be the major 7, the minor 7, and the dominant 7 chords.

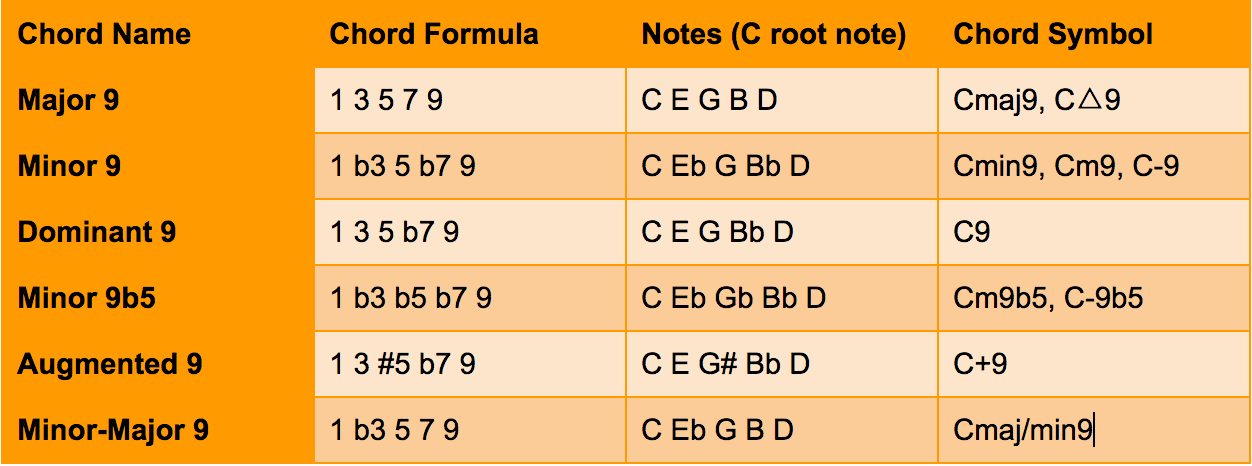

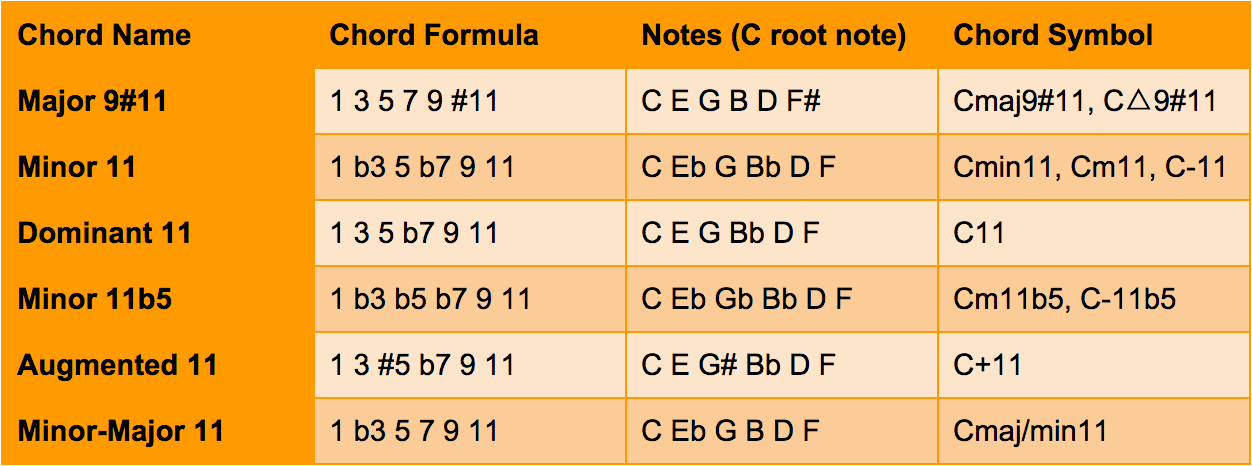

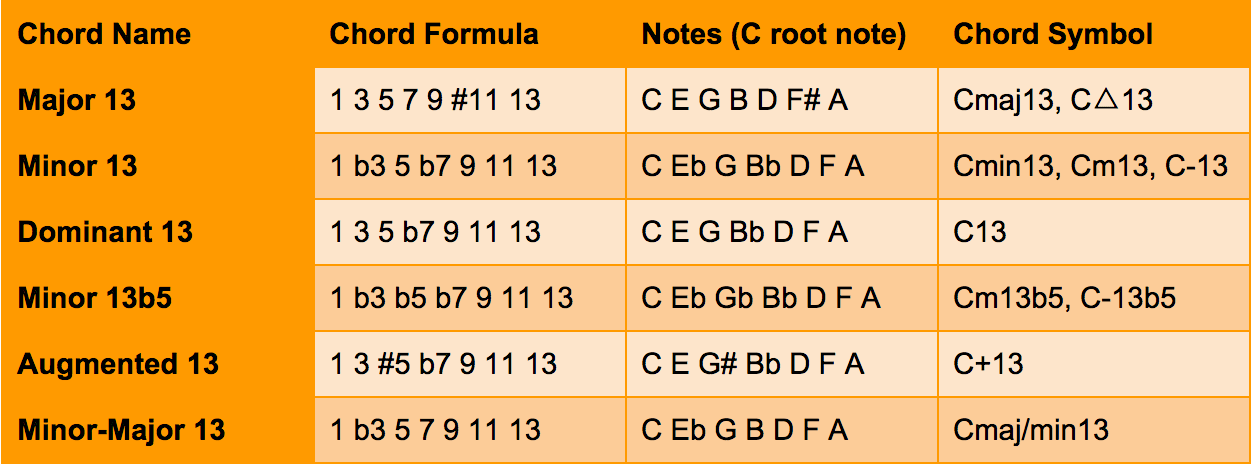

What happens if we keep stacking thirds?

We build chords by stacking thirds, and we can continue to do this until we run out of notes. If we count three notes up from 7, we add a 9th (the octave repeats itself, so the 9th will be the same note as the 2nd, only an octave higher). Three notes up from 9 gives us an 11th, and three notes up from 11 adds a 13th. If we are playing a 9th chord, we replace the 7 in our chord symbol with a 9. We replace the 7 with and 11(for an 11th chord) and a 13 (for a thirteenth chord) in the same way. When a chord symbol has a 9 instead of a 7, we assume that the 7 is included. Likewise, if a chord symbol has a 13, we assume that the 7, 9, and 11 are all included.

Note that we usually sharpen the 11th scale degree when we are building major quality chords using the 11th scale degree.

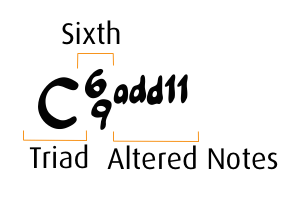

Step 3: Alter some notes

The third part of the chord symbol indicates any alterations that have been made to the rest of the notes in the chord. We read the Cm7b5b9 example as a Cm7 chord (1 b3 5 b7) that has had the 5th scale degree flattened (1 b3 b5 b7), and has had a b9 scale degree added to it (1 b3 b5 b7 b9). Note that if we had wanted to add a normal 9th scale degree (i.e. not flattened), we would have changed the ‘7’ in the chord symbol to a ‘9’. If we had done this, the chord symbol would have read ‘Cm9b5’.

Sometimes, we might decide to add scale degrees to a chord without altering them or building on top of a 7th. For example, adding a 9th scale degree to a major triad would result in a ‘Cadd9’ chord (1 3 5 9). Note that this is different from a Cmaj9 chord because it doesn’t have the 7th scale degree.

Other chord types

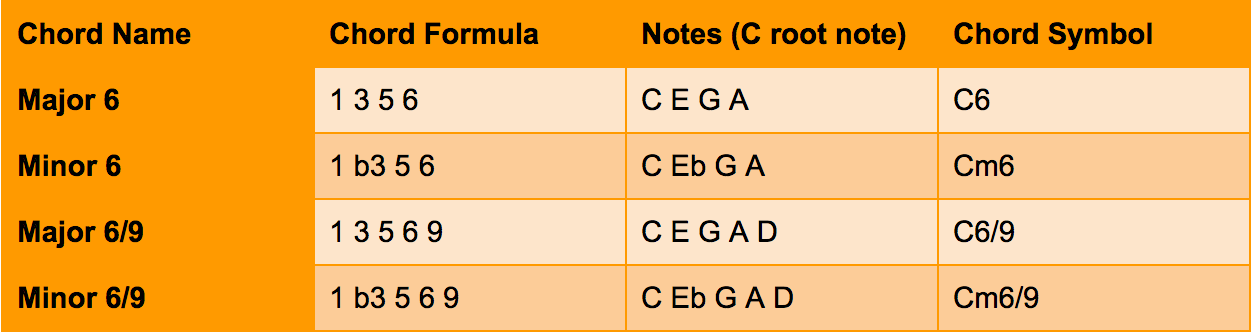

Occasionally, we will come across some chords that don’t fit exactly into the steps above, even though they behave in a similar way.

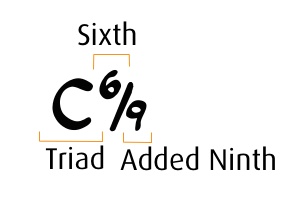

‘6’ Chords

We add the 6th scale degree to basic triads in a similar way to the how we added the 7th scale degree. The difference is that the 6 is never flattened, and because a 6 chord does not contain a 7th scale degree, we cannot replace the 6 in the chord symbol with a 9 when we add a 9th scale degree like we did with seventh chords. If we wanted to play a major 6 chord with an added 9th scale degree, we would have to write ‘C6/9’. Again, because a 6 chord doesn’t have a a 7th scale degree, any additional notes have to be specified in the chord symbol. You might see the 6/9 chord written with or without the slash in the chord symbol.

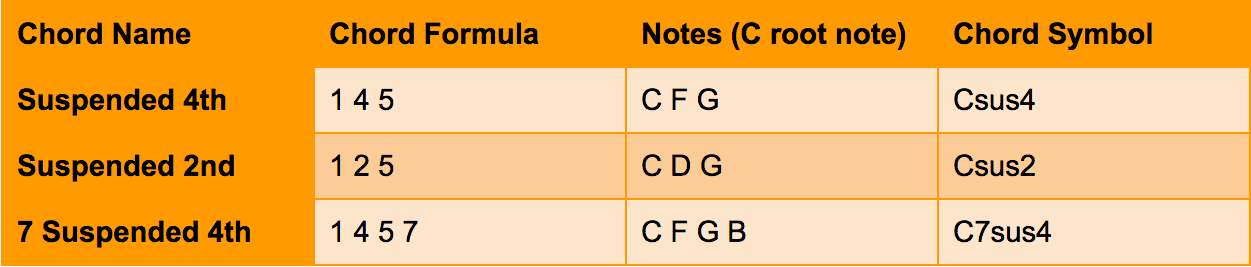

Suspended Chords

The point of a suspended chord is to resolve to a triad. There are two types of suspended chords: the suspended 4th (sus4), and the suspended 2nd (sus2). When we add ‘sus4’ or ‘sus2’ to the altered notes part of our chord symbol, it indicates that we are to remove the third and replace it with either a 4th scale degree (sus4), or the 2nd scale degree (sus2).

Slash Chords

A slash chord indicates that you play a chord with an alternative note in the bass. The diagram below tells us to play a C major triad with the note ‘E’ in the bass.

Learning how to read chord symbols and construct chords can seem pretty challenging. However, when you break it down, you realise that chord symbols behave in a very predictable way. As long as you remember what each part of the chord symbol is telling you to do to the chord formula, you’ll never be caught wondering what notes to play!